RabbitMQ Internals - Credit Flow for Erlang Processes

With a queueing server like RabbitMQ there’s the potential problem of having publishers that out pace consumers, creating the issue of queues that start to back off and get filled with messages. If this problem is not taken into account, RabbitMQ will run out of disk space at some point. While this is more off an issue for the app that uses RabbitMQ than of RabbitMQ itself, the broker still needs to provide a way to prevent the system from going down under such circumstances. To deal with this problem RabbitMQ implements the concept of credit flow for communication between Erlang processes.

RabbitMQ has a reader process, implemented inside the rabbit_reader.erl module that takes care of reading data from the network and convert it to AMQP commands that are dispatched to the rabbit_channel.erl module / process. So for example whenever you publish an AMQP message via basic.publish, the rabbit_reader will interpret that command and send it over to the rabbit_channel process to handle it properly. To do that an Erlang message is sent between the rabbit_reader process and the rabbit_channel. But what happens if your app goes rogue and overwhelms the RabbitMQ server with more messages from what it can process? Could we prevent that? Enter credit_flow.erl.

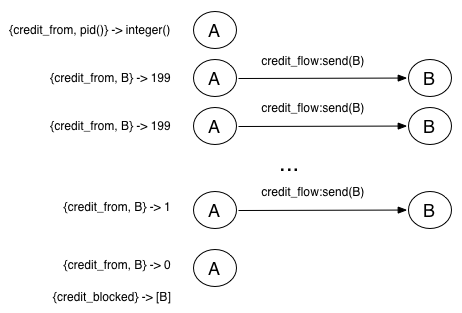

With credit_flow what happens is that a process that wants to use the flow mechanism has a certain amount of credit for sending messages to a particular process. That credit is diminished with every message sent via the flow mechanism. After X messages, the receiver process will grant more credit to the sender so it can continue sending messages in case it got blocked at some point. How does it all works?

First we have what is called a credit specification in the form of a tuple like:

{InitialCredit, MoreCreditAfter}For example unless you specify different values when using the credit_flow API, your process will start with a default credit of {200, 50}. That is it can send 200 messages until it runs out of credit. How does process A gets more credit either before or after credits runs down? Let’s say that process A is sending messages to process B. Every time B processes a message sent by A it will “ack” it back. Once it acks MoreCreditAfter messages from process A, then it will grant more credit to process it. Let’s see how this is implemented taking the interactions between rabbit_reader and rabbit_channel as our example.

Whenever rabbit_reader parses a protocol command that has content, like a basic.publish, it will pass it onto the rabbit_channel like this:

rabbit_channel:do_flow(ChPid, Method, Content)And here’s how’s rabbit_channel:do_flow/3 is implemented:

do_flow(Pid, Method, Content) ->

credit_flow:send(Pid),

gen_server2:cast(Pid, {method, Method, Content, flow}).As you can see the rabbit_channel module takes care of telling the credit_flow module to account for the message received from rabbit_reader by calling credit_flow:send(Pid) where Pid is the process id of the current channel. While this is a bit confusing at first, what happens is that rabbit_reader, in this case the message sender, will track how many messages it has sent to the rabbit_channel process.

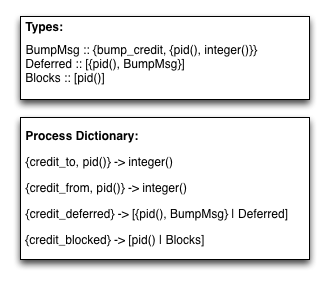

Now, where is this information tracked? The credits are being tracked on the process dictionary. The credit_flow module will call the get/1 and put/2 BIFs to get and update those values.

Let’s backtrack a bit and see how this works.

Keeping track of credits

As we can see from the code, the rabbit_reader will call rabbit_channel:do_flow/3 and finally that function will call credit_flow:send/1 which will decrease the credit for the reader process. The thing to understand here is that while the function call to credit_flow:send/1 happens inside the rabbit_channel module, we are still inside the rabbit_reader process. Only after the gen_server2:cast(Pid, {method, Method, Content, flow}) is handled, we are going to be into the memory space of the channel process. Therefore when credit_flow:send/1 is called, the credit decreased operation is tracked inside the sender, in this case the rabbit_reader process dictionary.

The key used to store that information is like this {credit_from, From}, where From is the Pid of the message receiver, in this case the channel (The previous image shows all the dictionary keys used by the credit flow mechanism). If the information stored in the {credit_from, From} key reaches 0 then the process that owns that dictionary will get blocked, in our example that process would be the rabbit_reader process. Here’s the implementation of credit_flow:send:

send(From, {InitialCredit, _MoreCreditAfter}) ->

?UPDATE({credit_from, From}, InitialCredit, C,

if C == 1 -> block(From),

0;

true -> C - 1

end).

Now keep in mind that the rabbit_reader process could have been sending messages to various processes at the same time where is possible to reach a state where rabbit_reader is blocked by more than one process. Therefore each process keeps a list in its dictionary where it tracks which processes pids are blocking it, if any:

credit_blocked -> [pid()]Acknowledging messages

We said that whenever a process handles a message it will ack the message via the credit_flow system, possible granting more credit:

ack(To, {_InitialCredit, MoreCreditAfter}) ->

?UPDATE({credit_to, To}, MoreCreditAfter, C,

if C == 1 -> grant(To, MoreCreditAfter),

MoreCreditAfter;

true -> C - 1

end).In this case the rabbit_channel process will keep track of how many messages it has ack’ed from a particular sender (in our case the rabbit_reader). The key used to keep that message in the dictionary is {credit_to, To} where To is the pid of the sender. After MoreCreditAfter messages has been received it will grant more credit to the sender.

Granting more credit

To grant more credit a process will send a message of the form {bump_credit, {self(), Quantity}} to the process that should receive the credit, where self() points to the process granting credit. But granting credit is not an easy task tho. Why? Because to grant more credits a process needs to send a message to whichever process it is trying to send credits. While sending a message is not a problem, it could happen that a process has been blocked, and therefore it can’t send messages. What happens here? The blocked message will keep that credit for later inside the dictionary pointed by the credit_deferred key where it’ll keep a list of {Msg, To} tuples. The Msg in this case has this signature: {bump_credit, {self(), Quantity}}.

Handling bump credit messages

When a process receives a bump_credit message it needs handle it by calling credit_flow:handle_bump_msg/1 passing the received message over. Because we control is on the process that’s handling the bump_credit message, we can access the dictionary of that particular process. The process will update the {credit_from, From} key, where From is the pid of the process that granted credits. So if the credits goes above zero, then the process will be unblocked for that particular receiver. If by calling credit_flow:unblock/1 the list of credit_blocked goes empty, then the process can resume sending messages. Also credit_flow:unblock/1 will take care of sending all the messages that were saved for later in the credit_deferred list. This means we could potential have a chain of blocked processes. Here’s the code for handle_bump_msg.

handle_bump_msg({From, MoreCredit}) ->

?UPDATE({credit_from, From}, 0, C,

if C =< 0 andalso C + MoreCredit > 0 -> unblock(From),

C + MoreCredit;

true -> C + MoreCredit

end).Unblocking a process

When unblock/1 is called what will actually happen is that the pid of the process granting credits will be removed from the list of pids that’s being kept in the credit_blocked key. So if B and C are blocking A this is what will happen if B unblocks A.

%% We are operating on process A dictionary.

get(credit_blocked) => [B, C].

unblock(B).

get(credit_blocked) => [C].In this particular case A will still remain blocked until C grants more credit to it. Once that happens then A will be free again to send messages. At this point process A will take care of his credit_deferred list, sending bump_credit messages to those process that were on the deferred list.

Peer down

The credit flow mechanism also handles the case of a peer process going down. Keep in mind that a process keeps track of credits in a per receiver pid basis. So if the receiver dies, then the process has to remove the entries for that particular process. Those entries where kept in the {credit_from, Pid} used by credit_flow:send. Also because the process might have received messages from the dead process, then it has to delete the {credit_to, Pid} key.

Conclusion

When we have systems that have queues of any kind, we need to be aware that if our producers outpace our consumers, then those queues will grow infinitely. In the case of Erlang, each process will have it’s own mailbox and if a process can’t keep up with the amount of messages is receiving, at some point everything will break havoc. By having a system like the credit_flow in place, as used by RabbitMQ, we can prevent those scenarios and react accordingly.

PS: If you wonder how the ?UPDATE macro works, take a look at its implementation here. I leave it as an exercise to the reader to understand how that work and I’ll explain it in a future blog post.

More articles on the RabbitMQ internals series:

- 04 Sep 2013 RabbitMQ Internals - Validating Erlang Behaviours

- 02 Sep 2013 RabbitMQ - Sanitizing user input in Erlang

- 01 Sep 2013 RabbitMQ - Validating User IDs with Erlang Pattern Matching

- 29 Aug 2013 Erlang Pattern Matching, Protocols and RabbitMQ