Replication Techniques: some papers and an interesting book

In this post I would like to share some papers I’ve found this week, along with a book on database replication techniques.

This week I started doing some research about replication in distributed systems. My first stop was a book called Replication Techniques in Distributed Systems which has quite a few interesting quotes about what are distributed systems, specifically, how we should always expect failures when dealing with these kind of systems, for example:

A distributed computing system, being composed of a large number of computers and communication links, must almost always function with some part of it broken.

And continues:

Over time, only the identity and number of the failed components change.

And that’s literally just the first paragraph of the book’s introduction.

I joked on Twitter that this book is a manual of “how to drop the mic while discussing distributed systems”.

If we know the system will have failures, we need to think about how to achieve fault tolerance and there’s where the discussion of the book lead us to by presenting replication techniques.

It’s interesting to see how the authors mention that from the point of view of applications, the source of the failures, whether they are bugs or mechanical failures, they just don’t matter. The application (the user of the distributed system) simply cares about what are the reliability and availability properties of the system.

Availability vs Reliability

A reliable system is not necessarily highly available.

The book explains the difference between availability and reliability. A system is “highly available” if its fraction of downtime is very small; on the other hand, a system is reliable if it manages to stay up for the amount of time required to perform computations in order to serve requests.

For example, a car can be highly available, that is, it always goes on when you turn the ignition, but it might have a failure in the radiator, (it overheats), so is not able to function long enough to take you were you wanted to go, that is, is not reliable.

In short, a system is reliable to the extent that it is able successfully to complete a service request, once it accepts it. To the end user therefore, a system is perceived reliable if interruptions of on-going service is rare.

Another pearl from the book:

As the number of sites involved in a computation increases, the likelihood decreases that the distributed system will deliver its functionality with acceptable availability and reliability

The book then goes on to describe various protocols used for data replication on distributed systems, putting an emphasis that network partitions do happen.

Related Papers

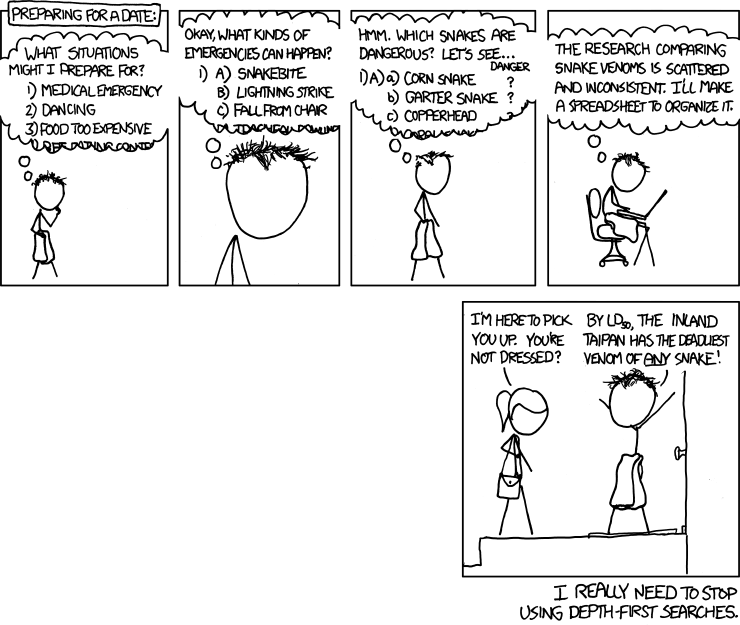

While reading the first chapters from the book I had the Depth First Search problem that this XKCD comic clearly demonstrates:

I basically wanted to read every paper mentioned in that book, specifically, since they seemed to present some context on how network partitions have been treated historically in computer science.

So I found this 1984 paper by Susan Davidson and Hector Garcia-Molina:

Consistency in a Partitioned Network: A Survey

This paper has the classical insights on network partitions, like:

The design of a replicated data management algorithm tolerating partition failures is a notoriously hard problem.

Typically, the cause or extent of a partition failure can not be discerned by the processors themselves.

In addition, slow responses from certain processors can cause the network to appear partitioned even when it is not

Then the paper presents some curious use cases from back in the ’80s. One of them mentions that a system had “170 transactions per second at peak time”.

Let’s look at this quote:

Since it is clearly impossible to satisfy both goals simultaneously, one or both must be relaxed to some extent depending on the application requirements.

In the context of this quote both goals means correctness and availability. So we could stretch this (and maybe close one eye while we are at it) and we can smell a hint to what today we call the CAP theorem. Pick any two.

So, it was all good and shinny until I read;

As far back as 1977, partitioned operation was identified as one of the important and challenging open issues in distributed data management

So, erm, there’s another paper I should be reading? I go and search for that paper until I find it:

Introduction to a System for Distributed Databases SDD-1

Lo, and behold! It was the paper introducing SDD-1, or in other words “the first general-purpose distributed DBMS ever developed.”.

At this point, I skim over that paper and try to get back to the book. It was a bit late, so I decided to gloss over the the book to see what was there. One of appendices has a reading list on the various topics presented in the book. One of such lists is called “Replication in Heterogeneous, Mobile, and Large-Scale Systems”. The first paper there sounded a bit, familiar.

Primarily Disconnected Operation: Experiences with Ficus

This paper basically presents what we today call “Offline First” but with the terminology used back in the ’90s, 1992 to be precise. For example, let’s see this use case of their solution:

Home Use: Imagine having a machine at home which replicates most of the environment you use in the office. When you commute, your machine at home dials into the office, pulling down any changes made that day. By the time you get home, the machine there is up to date and you can work in the evening. When you are done for the night, your machine dials in to the office and reconciles changes again, uploading all your changes. While primarily disconnected the machine at home is functioning almost as if it were constantly connected.

So there it is, the past showing us the future. Smart individuals way before us faced some of the same problems that appear novel today. The buzzwords have changed, but the problems remained the same.

nihil sub sole novum.